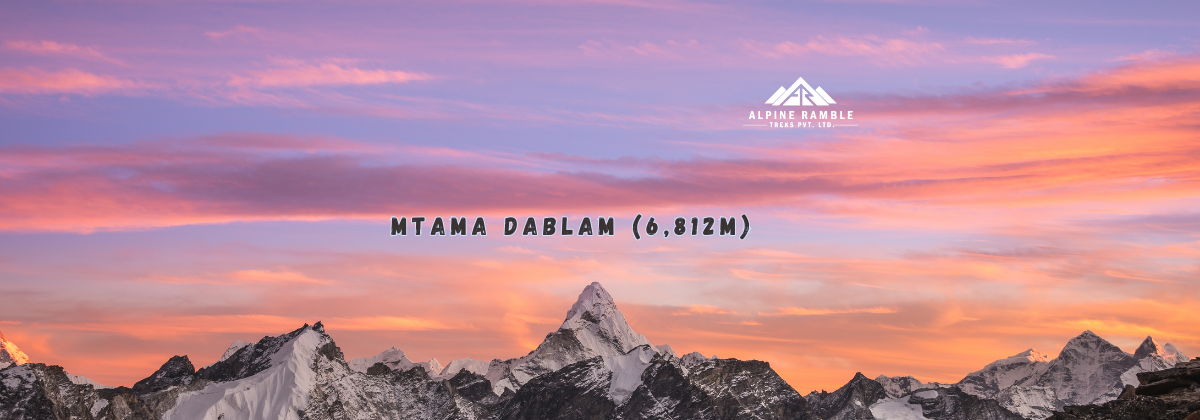

Looking Back at Ama Dablam Legacy

Discover the rich history and modern significance of Mt Ama Dablam, a mountain revered for its beauty and cultural heritage.

Solukhumbu was not always the homeland of the Sherpa Migration to Solukhumbu. Historically, this region was home to various ethnic groups long before the arrival of the Sherpas. The term “Sherpa” refers to an ethno-linguistic group from the Tibeto-Burman language family, not an occupational title linked to mountaineering. The migration of Sherpa communities to Solukhumbu represents a multi-generational movement, shaped by complex historical narratives that predate modern mountaineering.

The story of Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu is rooted in the regions of Kham and Tsang in Eastern Tibet, their ancestral homelands. The linguistic roots of the Sherpa language Tibeto-Burman connect them to a broader heritage. Their society is organized around various clans, such as the Minyagpa, Thimmi, Salaka, and Paldorje.

The religious landscape of these early communities included influences from Nyingma Buddhism Sherpa and remnants of Bon traditions. This reflects a rich spiritual tapestry that accompanied them on their journey.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Ancestral Homelands | Kham and Tsang, Eastern Tibet |

| Linguistic Roots | Tibeto-Burman language family |

The term ‘Sherpa’ is often mistakenly viewed as merely an occupational label. However, it is fundamentally an ethno-linguistic identifier for a people whose roots lie in Eastern Tibet. The Sherpa language, a member of the Tibeto-Burman family, showcases this connection.

The Sherpa Migration to Solukhumbu was not a singular event but a complex, multi-generational movement. This migration originated from the Kham and Tsang regions of Tibet, where clans like the Minyagpa, Thimmi, Salaka, and Paldorje trace their lineage.

Oral histories, preserved through generations within the monasteries of the region, recount the intricate genealogies of these clans. Lacking written records, the Sherpa people have relied on their rich oral traditions to remember their ancestry. This preservation of identity is evident in their language, customs, and social structures, which have persisted despite the encroaching influences of neighboring cultures.

| Clan Name | Region of Origin | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|

| Minyagpa | Kham | Known for their pastoral skills and trade networks. |

| Thimmi | Tsang | Renowned for their agricultural practices and land management. |

| Salaka | Kham | Famous for their spiritual leadership and monastery affiliations. |

The migration of Sherpa communities to Solukhumbu from the 13th to 15th centuries was driven by multiple factors beyond economic needs. Political instability in Tibet, marked by local conflicts and oppressive taxation, forced many families to seek refuge in the valleys south of the Himalayas. This quest for safety coincided with the need for better pastures for yak herding and participation in trans-Himalayan trade, essential to the Sherpa way of life.

Religious motivations significantly influenced this migration. Sherpas sought auspicious lands known as beyul, believed to be blessed and safe havens. This migration was gradual, often occurring in waves as clans like the Minyagpa and Thimmi faced challenges in their homeland.

| Factor | Description | Impact | Time Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political Instability | Conflict in Tibet led to unsafe conditions. | Increased migration southward. | 13th-15th Century |

| Taxation Pressures | Heavy taxes imposed by local rulers. | Economic strain on families. | 14th Century |

| Religious Aspirations | Search for auspicious beyul lands. | Motivated spiritual journeys. | 13th-15th Century |

| Environmental Factors | Need for better grazing lands. | Secured livelihoods through pastoralism. | 14th Century |

Seasonal movement patterns were integral to the migration. Families timed their journeys to coincide with favorable weather, ensuring the safety of their livestock and the preservation of their cultural practices. The risks involved were substantial; Sherpa migration faced the dual threats of altitude sickness and unpredictable weather, all while navigating remote and often isolated paths.

Each family carried essential items, including livestock, seeds for cultivation, ritual objects reflecting their spiritual beliefs, and texts preserving their cultural heritage.

| Route | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Nangpa La Pass | Altitude sickness, severe weather |

| Adjoining passes | Isolation, difficult terrain |

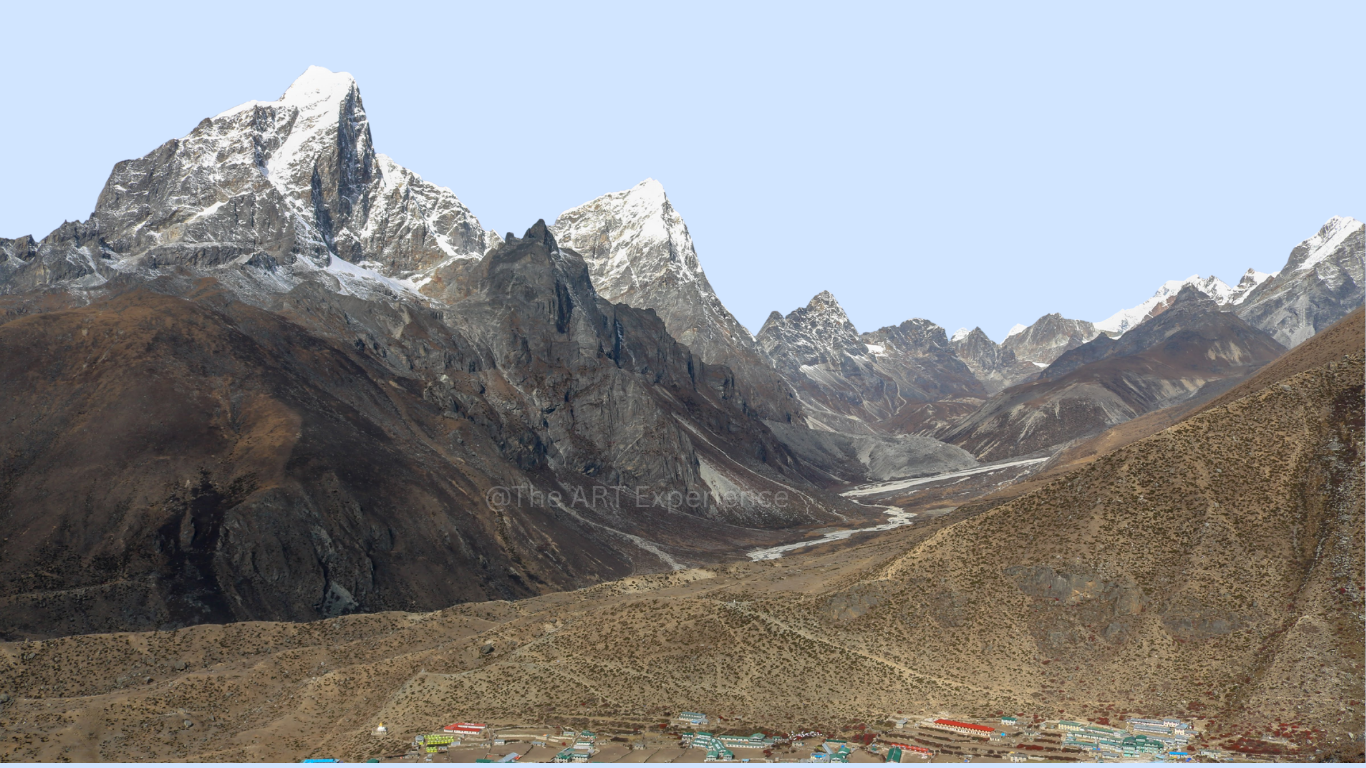

The valleys of Solukhumbu are known for their breathtaking landscapes and abundant resources. These features created an ideal environment for early Sherpa migration from Tibet. The region's natural elements, like plentiful pastureland and fresh water, were essential for yak herding, a primary livelihood for the Sherpa people Nepal. Settlements emerged in areas such as Khumbu, Pharak, Thame, and Pangboche, each contributing to the region's cultural richness.

Early Sherpa migration communities were not isolated. They interacted with existing inhabitants, including the Rai and other hill groups, fostering a complex network of negotiation and coexistence. The idea of 'empty land' is a misconception; the Sherpas navigated a landscape already shaped by various ethnic groups. Customs for land use developed, emphasizing communal pasture rights and clan-based allocation, ensuring sustainable coexistence that honored both the land and its original inhabitants.

| Settlement Area | Significance | Established |

|---|---|---|

| Khumbu | Key area for trade and cultural exchange | 14th Century |

| Pharak | Rich pastoral land, early agricultural practices | 15th Century |

| Thame | Religious center, home to important monasteries | 14th Century |

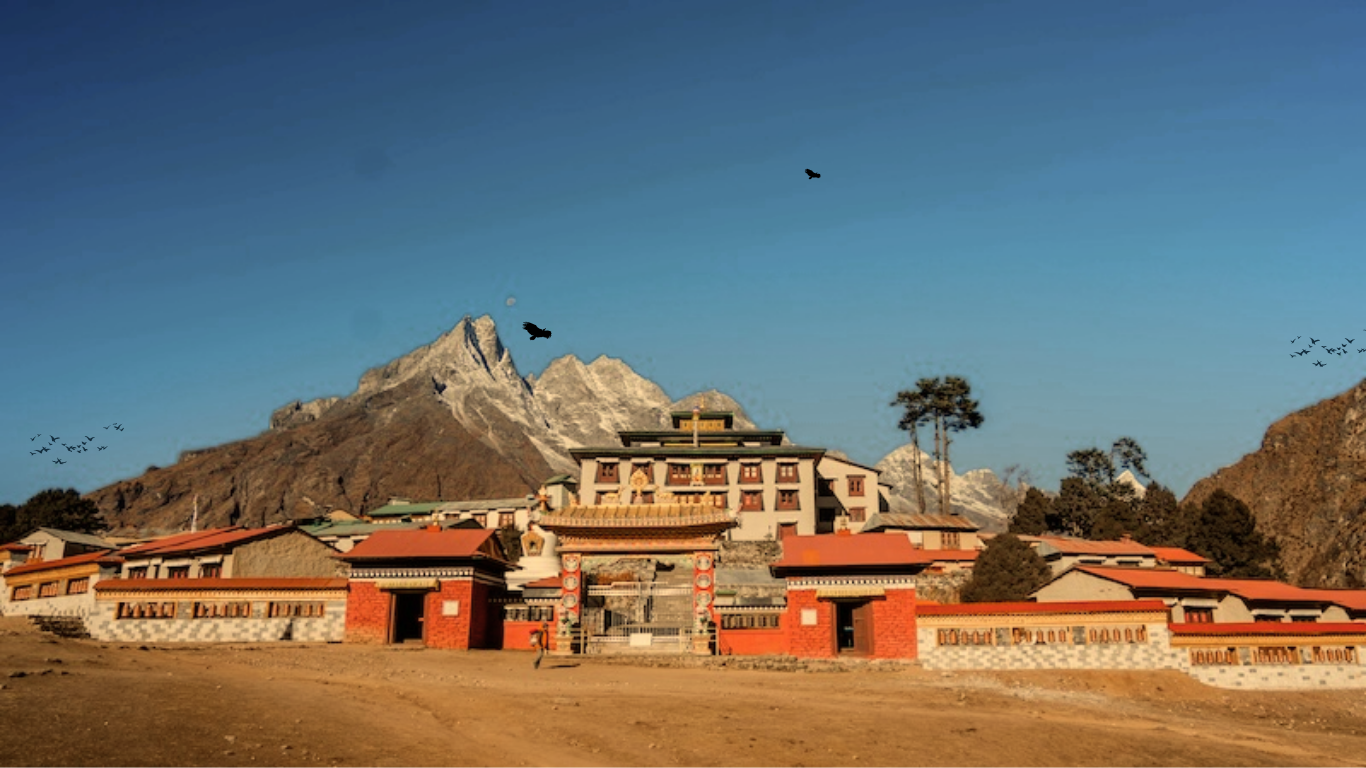

As Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu unfolded, the founding of monasteries became a pivotal aspect of their cultural identity. Key religious sites, such as Pangboche Monastery and Thame Monastery, emerged as spiritual centers and legitimizing forces for Sherpa presence in this region. Dating back to the 17th century, these monasteries became repositories of Nyingma Buddhism, preserving teachings and practices integral to Sherpa life.

The role of lamas in these monasteries was crucial in affirming the Sherpa's spiritual and cultural connection to the land. They significantly contributed to community rituals and festivals, reinforcing the notion of yul-lha, or sacred mountains, as protectors of the Sherpa people. This cultural anchoring transformed Solukhumbu into a homeland imbued with spiritual significance, where each mountain and valley became associated with local deities and ancestral spirits.

Festivals such as Lhosar, marking the Tibetan New Year, and Chhewar, a rite of passage for young Sherpa boys, were celebrated with great fervor in these monasteries. Through these rituals, the Sherpas honored their traditions and reinforced community bonds, ensuring their identity remained intact amidst the challenges of migration and settlement.

The oral histories preserved within these monasteries provide invaluable insights into the clan-based society of the Sherpas. They allow the Sherpas to trace their lineage and maintain a strong sense of identity. This oral tradition, alongside the teachings of the lamas, plays a critical role in transmitting Sherpa culture and values across generations, ensuring that despite external influences, the essence of Sherpa identity remains resilient.

The presence of these monasteries illustrates that the Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu was not merely a physical relocation but a profound spiritual journey. It integrated their cultural heritage with the new landscape they came to inhabit. Read on to discover how the Sherpas navigated their identity through these sacred spaces and rituals.

The Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu is deeply intertwined with a complex social structure that preserves their identity. This identity is maintained through endogamy, clan-based customs, and a resilient cultural framework. The Sherpa people, primarily from eastern Tibetan regions like Kham and Tsang, possess a rich heritage that transcends mere occupational labels. The term 'Sherpa' itself is ethno-linguistic, derived from 'Shar' meaning 'east' and 'pa' meaning 'people', indicating their origins.

Endogamous practices among Sherpa clans, such as Minyagpa, Thimmi, Salaka, and Paldorje, are pivotal in preserving their cultural integrity. Marriages within these clans reinforce social bonds and maintain linguistic continuity. The Sherpa language, part of the Tibeto-Burman family, remains vital to their identity, allowing for the transmission of oral histories and traditions despite surrounding influences from Nepali culture.

Architecturally, Sherpa villages exhibit a distinct style characterized by stone houses with flat roofs, reflecting their adaptation to the harsh Himalayan environment. Their culinary practices are unique, featuring traditional dishes like 'thukpa' (noodle soup) and 'momo' (dumplings), integral to their communal identity. Furthermore, the oral law, or 'kha', serves as a guiding principle in social conduct, ensuring customs and traditions are upheld across generations.

Trade networks established between Tibet and Nepal significantly fortified Sherpa identity. These routes facilitated the exchange of goods, such as salt and textiles, and cultural interactions that enriched their heritage. The Sherpa's role as traders and pastoralists predates the modern narrative of them solely as mountain guides, underscoring their cultural self-sufficiency and economic resilience.

As the Sherpa communities of Solukhumbu navigated their environment's complexities, their collective identity evolved yet remained firmly rooted in the practices and customs that define them. This resilience is a testament to their ability to adapt while preserving the essence of what it means to be Sherpa.

The narrative surrounding Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu often overlooks the region's economic life prior to the influx of foreign trekkers and climbers. The Sherpa people Nepal were not merely guides; they engaged in a vibrant economy rooted in trade and pastoralism. Historically, Sherpa communities thrived on the trade routes connecting Tibet and Nepal, particularly in salt, barley, and livestock.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Sherpas operated extensive yak caravans that traversed the rugged terrain of the Himalayas. These caravans transported goods such as salt from Tibet, a crucial commodity in the diet of the hill communities. The Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu was significantly influenced by their role as traders, with families migrating in search of better trading opportunities and more accessible pastures for their yaks.

In addition to trade, agriculture played a vital role in the economic framework of the Sherpa communities. The fertile valleys of Solukhumbu provided ample opportunities for farming, where barley and potatoes became staple crops. The Sherpa people practiced a form of communal land use, allowing them to allocate pastures and farming lands among clans, fostering cooperation and shared responsibility.

Moreover, Sherpa culture was rich in traditions and rituals that revolved around their economic activities. Annual festivals celebrated the harvest and the successful completion of trade expeditions, reinforcing communal bonds and cultural identity. The Sherpas’ ability to adapt to their environment and maintain self-sufficiency laid the groundwork for a robust social structure long before the advent of modern mountaineering.

This historical context of Sherpa life challenges the prevailing stereotypes that portray them solely as guides for foreign expeditions. Understanding the pre-Everest Sherpa society reveals a complex tapestry of trade, pastoralism, and cultural richness. Read on to discover how these elements shaped their identity and influenced their interactions with the outside world.

The closure of the Tibet-Nepal border in the early 1960s marked a significant turning point for Sherpa communities in Solukhumbu. Previously, the Sherpas had enjoyed a fluid exchange of goods and culture with Tibet, a relationship that was abruptly severed. This closure not only restricted traditional trade routes but also altered the socio-economic fabric of Sherpa society, compelling many to seek new avenues for livelihood.

As foreign expeditions began to arrive in the region, the Sherpas found themselves at a crossroads. The influx of climbers and trekkers from the West, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s, introduced a new economic dynamic. Guiding, once a communal and informal practice, gradually transformed into a formal profession. Sherpas who had previously identified primarily as traders and pastoralists began to embrace roles as mountain guides, a shift that would redefine their social identity.

However, this transformation was not without its challenges. The rise of guiding as a profession led to new hierarchies within Sherpa society, as those who could speak English and navigate the demands of foreign clients gained prominence. This created a dichotomy between traditional ways of life and the emergent economy focused on tourism and expedition services. While some Sherpas prospered in this new environment, others struggled to adapt, leading to a complex interplay of cultural preservation and economic necessity.

Furthermore, the arrival of foreign expeditions brought about a re-evaluation of Sherpa identity. The once-strong ties to their historical narratives and pastoral roots began to fray as the allure of modernity and economic gain took precedence. Sherpas were increasingly perceived through the lens of their roles as guides, overshadowing their rich cultural heritage and contributions to the Himalayan landscape. This shift in perception necessitated a reevaluation of what it meant to be Sherpa in a rapidly changing world.

As the 20th century progressed, the Sherpas of Solukhumbu navigated a delicate balance between embracing new opportunities and preserving their cultural identity. The economic changes brought about by foreign expeditions were profound, but the essence of the Sherpa experience remained deeply rooted in their historical migration to this Himalayan homeland. Understanding this evolution is crucial in comprehending the full narrative of Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu and the resilience of their culture amidst the tides of change.

The narrative of Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu is not merely a historical account; it is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the Sherpa people. Despite the myriad challenges faced over centuries, from environmental shifts to sociopolitical upheavals, Sherpas have managed to maintain a distinct identity rooted in their Tibetan origins.

As the Sherpa communities settled in Solukhumbu, they brought with them not only their language, a member of the Tibeto-Burman family, but also their rich cultural practices and clan structures. The clans such as Minyagpa, Thimmi, and Paldorje have played a crucial role in preserving their unique heritage. This preservation has been reinforced through oral traditions, which have been vital in maintaining their genealogical records in a region where written documentation was historically scarce.

Moreover, the Sherpa's spiritual connection to the land has been a cornerstone of their identity. Founding monasteries like Pangboche and Thame facilitated the integration of Nyingma Buddhism, further anchoring their cultural practices in the sacred geography of the Himalayas. Festivals and rituals are not merely celebrations; they are acts of sanctification that reaffirm their ties to the land and each other.

However, the arrival of foreign expeditions in the 20th century introduced significant changes. While tourism has transformed the economic structures of Solukhumbu, the Sherpas have navigated this transition by embracing new roles while striving to preserve their cultural integrity. The professionalization of guiding, once an occasional activity, has become a primary source of income. Yet, this shift raises questions about identity and the potential dilution of cultural practices.

In examining Sherpa history as migration history, one recognizes that the journey continues. The Sherpas remain custodians of a rich cultural legacy, navigating the complexities of modernity while holding steadfast to their roots.

The historical narrative of the Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu is deeply intertwined with the oral traditions that have been preserved over generations. These stories serve not only as a record of the past but also as a vital means of maintaining cultural identity amidst the challenges of time and external influences. The Sherpa people, who originally hail from the eastern Tibetan regions of Kham and Tsang, have relied on these oral histories to recount their lineage and the journeys that brought them to their Himalayan homeland.

Oral histories play a crucial role in the transmission of genealogical knowledge, particularly in a clan-based society where written records are scarce. The Minyagpa, Thimmi, Salaka, and Paldorje clans, among others, have their unique narratives that detail their specific migrations and settlement patterns in Solukhumbu. These stories are often recounted during community gatherings, rituals, and festivals, reinforcing a sense of belonging and continuity.

The significance of oral traditions extends beyond mere storytelling; they are a repository of cultural values, religious beliefs, and shared experiences that bind the Sherpa community together. For instance, tales of early Sherpa migrations often incorporate elements of Nyingma Buddhism and Bon, reflecting the spiritual landscape that influenced their journey. The concept of beyul, or sacred valleys, is frequently mentioned in these narratives, highlighting the Sherpas' search for auspicious lands that would provide safety and prosperity.

As the Sherpa people navigated the complexities of their migration, these oral histories also served as a means of preserving their language, a member of the Tibeto-Burman family, against the encroaching influences of neighboring cultures. Through stories, songs, and proverbs, the Sherpa language has remained a vital component of their identity, allowing them to maintain a distinct cultural presence in a rapidly changing world.

In this way, oral histories are not simply relics of the past; they are living narratives that continue to shape the Sherpa identity and community in Solukhumbu. As new generations emerge, the retelling of these stories ensures that the essence of Sherpa culture and history remains intact, a testament to their resilience and adaptability in the face of historical and contemporary challenges.

Monasteries have served as vital repositories of Sherpa history, documenting the intricate narratives of their migration to Solukhumbu. The monasteries of Pangboche and Thame, for instance, are not merely places of worship; they are the heart of Sherpa cultural memory. Established in the 17th century, these monasteries are steeped in the early Nyingma influences that shaped the spiritual landscape of the region.

Oral traditions preserved by lamas recount the journeys of Sherpa clans from their ancestral homelands in Eastern Tibet, particularly Kham and Tsang, to the valleys of Solukhumbu. These accounts are crucial for understanding the motivations behind the Sherpa migration, as they reflect both the socio-political dynamics of Tibet and the spiritual beliefs that guided these movements.

In addition to religious teachings, the monasteries have also played a pivotal role in maintaining the Sherpa language, which belongs to the Tibeto-Burman family. The preservation of linguistic heritage is intertwined with clan identities, as clans such as the Minyagpa and Thimmi have recounted their genealogies through oral history, ensuring that their cultural narratives endure despite the absence of written records.

The festivals and rituals held at these sacred sites further sanctify the landscape, transforming the physical geography of Solukhumbu into a homeland imbued with spiritual significance. Festivals like the Mani Rimdu, celebrated at the Tengboche Monastery, illustrate how Sherpa culture has been shaped by both historical migrations and religious practices.

As we delve deeper into the historical narratives encapsulated within these monasteries, we uncover layers of meaning that connect the past with the present, revealing the resilience of the Sherpa identity amidst changing circumstances. Read on to discover how these sacred spaces continue to resonate with the Sherpa people today.

The landscape of Sherpa identity today is a complex tapestry woven from threads of tradition and modernity. As the world has changed, so too have the lives and identities of the Sherpa people of Solukhumbu. The Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu, rooted in historical necessity and cultural resilience, has led to a unique identity that is now being challenged by globalization and external influences.

Historically, Sherpa identity was preserved through strong clan affiliations and endogamous practices, ensuring that ties to their Tibetan origins remained intact. The clans—such as the Minyagpa, Thimmi, and Salaka—have played a crucial role in maintaining cultural continuity. Despite this, the modern era has ushered in significant changes. The influx of trekkers and climbers since the mid-20th century has introduced new economic opportunities but also new challenges, as traditional lifestyles are increasingly influenced by external forces.

Language plays a vital role in the preservation of Sherpa culture. The Sherpa language, a member of the Tibeto-Burman family, continues to be spoken widely, yet there is a growing concern about its erosion as English becomes more dominant in education and tourism. This linguistic shift reflects broader societal changes where younger generations may prioritize global communication over local heritage.

Architectural styles, dietary practices, and even social customs are evolving. While traditional Sherpa homes are characterized by their stone structures and intricate woodwork, modern influences have led to the introduction of new building materials and designs. Similarly, while traditional foods such as tsampa and yak meat remain staples, the availability of international cuisine has diversified dietary habits.

Trade networks that once linked Tibet and Nepal have also transformed. The historical role of Sherpas as traders and pastoralists is now often overshadowed by the perception of them solely as guides for foreign climbers. This shift has implications for social structures and economic hierarchies within Sherpa communities.

As Sherpa identity continues to adapt in the face of modern realities, the essence of their cultural heritage remains a vital anchor. Understanding the Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu as a historical foundation rather than a mere footnote allows for a deeper appreciation of their contributions to the Himalayan cultural landscape. The Sherpas are not merely accessories to Everest; they are the builders of a rich and resilient culture that has withstood the test of time.

Read on to discover how the past informs the present and shapes the future of Sherpa culture.

The history of Sherpa migration to Solukhumbu is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of political, social, and environmental factors spanning centuries. As scholars continue to delve into this complex narrative, several areas warrant further exploration. These include the examination of oral histories preserved in monasteries, which provide insights into the clan-based society of the Sherpa people and their ancestral roots in Eastern Tibet, particularly in regions like Kham and Tsang.

Moreover, the linguistic aspects of Sherpa identity, grounded in the Tibeto-Burman language family, offer a fertile ground for research. Understanding how the Sherpa language has evolved and retained its unique characteristics amid surrounding Nepalese influences could illuminate broader patterns of cultural resilience.

In addition, the economic structures that existed in Solukhumbu before the influx of foreign expeditions present a critical area for investigation. Analyzing the salt trade routes and yak caravans that defined the pre-Everest Sherpa society will challenge contemporary stereotypes and highlight the Sherpa people as traders and pastoralists rather than mere guides.

Finally, the transformation of Sherpa identity in the 20th century, particularly in response to the closure of the Tibet-Nepal border and the arrival of foreign expeditions, deserves thorough scrutiny. This period marked a significant shift in social hierarchies and economic roles that reshaped the cultural landscape of the Himalayan region.

Ongoing research can deepen understanding of the Sherpas as builders of culture in the Himalayas, revealing their significance beyond the modern narrative of mountaineering.

Our content is based on reliable, verified sources including government data, academic research, and expert insights. We also reference reputable publishers and primary sources where appropriate. Learn more about our standards in our editorial policy.

ART Experience Reviews

Add media, drop your rating, and write a few words. Submissions go to the Review Manager for approval.

More reading selected from the same theme.